|

present Book Reviews For Amateur & Avocational Archaeologists |

|

|

present Book Reviews For Amateur & Avocational Archaeologists |

|

Southeast USA

Archaeology

Southwest United

States

Southeast United States

Mississippian Complexes

All Other United States

Mesoamerica and South America

International (Europe, Africa,

Asia, Caribbean)

Back to Main Book Review Index

|

| Home | Gallery | Latest Finds | Back to Main Book Review Index |

|

The Caddo Nation:

Archaeological &Ethnohistoric Perspectives by Timothy K. Perttula University of Texas Press 1997/2006 re-release ISBN# 0-292-76574-6 paperback This re-release in paperback of the The Caddo Nation is an important contribution to understanding this Indian society at the cusp of the historic period and its transformation. It presents “…through archaeological, historical, ethnographic and archival means the nature of contact and interaction between the Caddoan Indian peoples of Texas, Louisiana, Oklahoma, and Arkansas and Europeans ---especially the Spanish and French --- and the Euro-Americans.” First encounters with European cultures were not always from a point of weakness on behalf of the Caddoans. The Spanish in Texas actively courted “the Kingdom of the Tejas” not only out of missionary zeal but as also as a hedge against French incursions from the east, while the French sought them out as fur trading partners. As other Indian tribes found them to be a significant power in their own right, Europeans sought them as allies in bringing belligerent native peoples under control. The importation of new diseases wrought disaster of epidemic proportions on the Caddoans, weakening and disrupting their culture. Tribes pushed out from a new formed United States began competing for their territory, followed by white immigrants, until the waning remnants of this once powerful society were eventually consigned to the Indian country. Pertulla does a fine job of mining the vast trove of documents produced by the Spanish, French and American dealings with the Caddo peoples and then reinforcing them with the growing literature of related archaeological findings. Caddo culture (actually composed of over 25 distinct groups) produced a particularly rich archaeology record including large farming communities, mounds, sophisticated mortuary practices which include grave goods, ceramics, and projectile points. Commerce with the Spanish and French is particularly well documented, with lists of trade items and relative percentages presented to various local tribes included. One can then find examples of these trade items turning up in burial grounds (much of the work was done before the Native American Graves and Repatriation Act) and extrapolations of what this implies in the interplay of transcultural relations. The large number of maps, tables, graphs and site diagrams are all useful in explicating the nature of the works being described. Extensive discussions such as 18 dense pages on the “Implications and Consequences of European Acute Disease on Caddoan Populations” utilizing bioarchaeological and paleodemographic methodology are eye-opening not only in revealing the wide range of work done but in the number of questions that are then raised by the findings. These trend of presenting further prospects for investigations in carried through in the final section, emphasizing that good archaeology should raise at least as many questions as it seeks to answer. Though not a leisurely read, The Caddo Nation is a masterful integration of historic and archaeological archives, melding elements from both into a broader picture than either alone can present. An appendix offers some insight into the significance of “changes in the frequency and occurrence of pottery types, design motifs and arrow point caches” in chronological sequencing, and a foreword by Thomas Hester touches on the importance of the work of avocational archaeologists in Caddoan research. This is a volume of real value to any reader seeking to better understand how archaeology, anthropology and archival research are brought together to broaden our understanding of the scope of the interaction between Indian and European cultures from initial encounters onward. The Caddo Nation is available in paperback for a web-special price of $13.37 from the University of Texas Press web site by clicking here, where you can also find a table of contents and excerpts from the preface and introduction. If you are interested in visiting a Caddoan mound you can

visit Caddoan

Mound

State Historical Site in Cherokee County, Texas.

Several

extensive Texas Beyond

History

articles on Caddoan history and archaeology can be found on the Upper

Nasoni and Sha’chahdinnih

sites. reviewed

by

Charles

Swenson

|

|

People of the Shoals

by Kenneth E. Sassaman University Press of Florida 2006 1st edition ISBN# 0-8130-2945-7 cloth hardback A critical function of archaeological research is not only to properly excavate materials from ancient sites, but to use this information to put found materials into a broader context used to define the ancient society, to determine the daily life and interactions within a culture. Kenneth Sassaman tells us the story of the People of The Shoals, those who lived on the famous Stallings Island site, a national landmark located in the middle Savannah River 13km upstream from Augusta, Georgia. Here a complex and mysterious society lived, one which made, possibly the earliest examples of pottery in this part of the world some 5000 years ago. Sassaman engages us with a very informal telling of all of the known research done in the area and across the southeast US, meant to introduce us to his theories of how the People of The Shoals lived, and where the idea of pottery came from or evolved from. This kind of informal style, mixing hard data with interpretive portaits of the life of the Stallings people, is hard to put down. The amateur will be as interested in this book as the professional. The Stallings culture was very interesting indeed, surrounding their camps with large rings of discarded shells, the uses of which have not been clearly understood until recently. Modern formal excavation soon discovered many discrepancies in both the types of projectiles and pottery sherds found. Was it possible that the Stallings culture produced pottery because of influence from other groups of people living in the area? How does one go about proving or disproving this kind of idea? The author skillfully explores the topic, weaving a complex story of a culture engaged actively in trade with its neighbors. We learn about soapstone and its unique properties when used to heat water or in other cooking activities. Could the changing supply of high quality soapstone have precipitated the development of pottery? How was the network of trade established and how far a distance was material imported from? How did these interactions affect the Stallings people in other facets of their life? These are some of the questions the author attempts to answer in this book. People Of The Shoals is an engaging read, fascinating in the way the author shows how data from various digs can be pulled together to make interesting conclusions about the life of the ancients. People of the Shoals can be

ordered

direct from the publisher, for $39.95, by clicking here. reviewed

by

Bob

Wishoff

|

|

The Prehistory of

Missouri By Michael J. O’Brien and W. Raymond Wood University of Missouri Press 1st ed. 1998 ISBN# 0-8262-1131-3 oversized paperback Covering over 11,000 years of history and culture, The Prehistory of Missouri is the first updated compilation of Missouri archaeology in over 20 years. “This book is about variation in the archaeological record of one geographically defined spatial unit--- the state of Missouri--- which in the global scheme of things is but one speck on a planet that has been inhabited by tool makers for at least two million years. At that scale, Missouri’s record appears small and rather insignificant….Yet hundreds of archaeologists have passed through the state during the last century and a half, and others have spent their entire careers working on this tiny piece of the earth’s archaeological record.” And so begins a book that not only articulates what is known about Missouri archaeology, but one that takes great pains to also articulate a great deal generally about archaeology and its methods. This book is extremely well written and illustrated with over 250 line drawings and photographs. It is obvious from the style of writing and the tenor of the explorations, that the authors are all too happy to have this book in the hands of amateurs and avocationalists eager to learn more about this important region. Keeping with the theme of variation, for each segment of history, paleoindian, archaic, etc., the authors contrast and compare findings in Missouri with those elsewhere, fitting in their region’s archaeology into the bigger picture of North American life in ancient times. I really appreciate the chronological summaries that appear throughout the book, making it a bit easier to swallow the vast quantities of knowledge contained in this volume. The book shows and explains how most every conclusion drawn from research was obtained. Lithic and ceramic typology is explained in depth, once again not only individually, but placed within contexts both broad and regional. If pottery is your focus of interest, the myriad types found in Missouri, and the discussions in the book will definitely be of interest to you. It is clear here, too, that anthropology is not left out of Missouri’s prehistory. Patterns of settlement and subsistence and cultural traditions are given great weight and importance within discussions, making it clear that this is the main function of anthropology, of which archaeology is a subdiscipline. Throughout the book, many quotes and references are made to the extensive work done in Missouri by Carl H. Chapman and his wife, Eleanor, who together edited the last four summaries of Missouri archaeology. Their book “Indians and Archaeology of Missouri” (to be reviewed elsewhere in this website) still sells well and was designed for an amateur audience. The Chapmans spent the better part of their lives investigating Missouri archaeology and the authors obviously respect their observations and conclusions. The Chapmans were putting together the 4th book of their own summary of the region when they were tragically killed in an automobile accident. Nearly forty pages of references end

this impressive

book, leaving plenty of room for further inquiry. The Prehistory of

Missouri

is sure to be enjoyed by anyone interested in archaeology. It can be

ordered

direct from the publisher for $39.95 by clicking here.

reviewed

by

Bob

Wishoff

|

|

Of Caves & Shell

Mounds Edited by Kenneth C. Carstens and Patty Jo Watson University of Alabama Press 1996 1st ed. ISBN# 0-8173-0805-9 paperback The result of a 1989 conference in Tampa Florida to celebrate the life’s work of the co-editor Patty Jo Watson, this book is a collection of papers which disputes long held ideas that the Eastern Woodlands cultures were simple, homogenous and unchanging for thousands of years. What’s cool about this book is that all of the investigations done were re-analyses and integrations of all of the existing collected research into the area to date. A lot of that data was collected by pioneer ethnoarchaeologist Patty Jo Watson. There are twenty-eight Watson citations referenced in the fourteen papers in the book. Thus, Of Caves & Shell Mounds, is a fitting tribute to Watson’s amazing three decade career and should serve as a model for other researchers as an inspiring example of how to do excellent research without spending a fortune doing it, especially if you have high-quality work to draw upon. (Read more about this stellar researcher by clicking here) The focus of the book is work done in the Kentucky karst region, especially at the Mammoth Cave National Park, where studies have shown that the Indians of the region engaged in mining of a renewable resource, speleothem salt. This topic has been covered somewhat superficially in magazines such as Archaeology and others, but the essays in the book fill in all of the detail of what is known to date. This is really exciting work, illustrating one facet of the complexity of Late Archaic/Early Woodland culture in the area. The reader soon sees there was a rich culture afoot in this region. Gail E. Wagner’s paper on early plant domestication is a fascinating review and reassessment of Watson’s patient, dedicated studies which show “the effectiveness of interdisciplinary research projects” and which “have figured prominently in formulations of plant domestication and cultivation in the mid-continent.” Phillip DiBlasi’s paper details rock art found in dark sections of Kentucky caves, many done with charcoal, others scratched into the mud. Dark area cave rock art is just now coming into its own as a topic of interest and there is little to read on the topic, so this publication was most welcome to read. Another paper of interest is by Mary C. Kennedy and details the radiocarbon dating process, inventorying difficulties within the laboratory process which introduce a range of inaccuracies into the dating system. I hadn’t realized how many different problems can occur with samples, not from improper handling, but from the varying processes performed in the lab. Unlike many other collections of presented papers, this one is written in a style that is very easy to read. I read the book in nearly one sitting, intrigued by the straightforward style of the writing which drew me into the reasoning of the research. All of the essays were interesting… I could have written a much longer review, but I promised to keep these reviews "quick." This book is a classic-- Buy It! I write these reviews to point

readers toward

great books to read: Of Caves and Shell

Mounds

should be on your bookshelf! Order this book direct from the

publishers,

for $34.95, by clicking here.

reviewed

by

Bob

Wishoff

|

|

Indians and

Archaeology of Missouri By Carl H. and Eleanor F. Chapman University of Missouri Press 1983 5th printing ISBN# 0-8262-0401-5 paperback This well written and nicely illustrated book is in the fifth printing of a revised edition which first appeared in 1964, and it is easy to see why. The late husband and wife team of Carl and Eleanor Chapman combined his writing skills as a professor of anthropology and archaeology (he is considered by many as the father of Missouri archaeology) and her artistic skills in archaeology illustrations (she was Art Editor of The Missouri Archaeologist). Together they produced one of the best introductions to the prehistoric inhabitants of Missouri. Their presentation is very clear and straightforward, beginning with an introduction to archaeology in relation to Indians and a broader look at Indians in the Americas in general. They then move chronologically through the major developmental periods --- migration into the Americas, the Paleo-Indian, Dalton, Archaic, Woodlands, Mississippian, Proto-Historic and Historic, including those Indians who passed through Missouri on their expulsion from east of the Mississippi. The relative brevity of these chapters (most are under 10 pages) is compensated by a depth of writing which packs a surprising amount of cultural information along with descriptions of artifacts and their uses. Short bibliographies are set at the end of every chapter for ready reference to more in-depth material. Eleanor Chapman's accompanying drawings of projectiles and other artifacts such as tools, pottery, structures, maps and daily life are elegantly detailed with unobtrusive notations for gauging size. Several pages of representative diagnostic materials and their respective periods are also included. The chapter on ‘The Archaeological Survey of Missouri’ is of special interest to avocationalists, addressing questions such as “How do you know where to look for Indian sites and artifacts?”, “What do you look for?” and “How do you make a survey for archaeological sites?”. Although the information is directed towards Missouri specifically (fortifications, burial mounds and pottery), much of it can be applied most anywhere one is looking for sites. A generalized description of the methodology utilized by archaeologists is covered in ‘The Archaeologist at Work’ and offers insight into how sites are approached with an eye to preservation of information that is both given up and destroyed by the process of excavation. Anyone who hopes to practice any sort of amateur archaeology, especially diggers (a practice that is not advocated by the authors), needs to pay attention to the authors’ advice on the subject. “There are true amateur archaeologists who lack academic training but are capable of doing excellent archaeological work. These people are knowledgeable, and many are fully competent to conduct archaeological investigations in certain areas and specialties. Their instruction has usually been less intense and not so broad as that of the professional archaeologist upon whom they depend for the interpretation of their research…Relics from uncontrolled, random digging are out of context. They are almost completely valueless in determining the story they might have told if they had been properly recorded while in place.” The Chapmans have done an excellent

job of

telling the story Missouri’s rich prehistoric past reveals. It

does

so in a style which will appeal to more advanced archaeological

interests

as well as a wider audience and so the book includes a glossary to

clarify

necessary technical terms. Indians and

Archaeology

of Missouri can be ordered directly from

the

University of Missouri Press for $19.95 by clicking here.

reviewed

by

Charles

Swenson

|

|

The Paleoindian and

Early Archaic

Southeast Edited by David G. Anderson and Kenneth E. Sassaman University of Alabama Press 1996 1st ed. ISBN# 0-8173-0835-0 paperback In the Preface to the book, the authors write: “The year 1992 marked the 500th anniversary of the initiation of European colonization and settlement of the New World, and to many people, the year 1492 remains the date of the “discovery” of the Americas. In this volume, we celebrate the true discovery process, a record of exploration and human achievement of epic proportions that is emerging through archaeological research. Our focus is the first 3,500 years or so of human settlement in the lower southeastern United States, spanning the Paleoindian and Early Archaic cultural periods, from approximately 11,500B.P. to 8000 B.P. In the pages that follow, ideas and evidence about this time in the southeast are summarized, illustrating how our knowledge of these earliest Americans continues to develop. The geographic focus for our research comprises the area roughly south of the Ohio River—West Virginia—Pennsylvania area to just west of the Mississippi River.” While much new information has been gleaned from the archaeological record since this book was published it still remains an excellent work and will not disappoint the reader. The book is comprised of 24 papers broken into three sections, the first part, within nine papers, examines the various models of lifeways during the time period across the region. The second part of the book, comprising eleven papers, describes the archaeological record for the entire region, each paper covering one region. This is an exceptional synthesis for any book to undertake. The papers are truly interesting reads. Chapter 10, “The Need for a Regional Perspective” gives the reader an overview of thinking about archaeological knowledge and is very well written. The regional papers are liberally illustrated with many drawings, maps and photographs of relevant material. Part three of the book is made up of four commentaries – I liked “Modeling Communities and Other Thankless Tasks” by Dena Dincauze. “The seductive problem with modeling is that as you model on fewer and fewer data (i.e., go back into the past), models are typically more elegant because they are parsimonious and uncluttered. They are also notoriously imprecise.” A nearly seventy page reference section rounds out this useful, readable reference. If you are interested in Paleoindian and Early Archaic lifeways, add this book to your library. Order The

Paleoindian

and

Early Archaic Southeast direct from

the

publisher, for $34.95, by clicking here.

reviewed

by

Bob

Wishoff

|

|

Twelve Millennia

Archaeology of the Upper Mississippi River Valley By James A. Theler and Robert F. Boszhardt University of Iowa Press/Mississippi Valley Archaeological Center 2003 1st edition ISBN# 0-87745-847-2 paperback Twelve Millennia is a very enjoyable book to read. The authors have taken great pains to synthesize a huge amount of research material into a set of essays that anyone can understand and organized them into a logical picture of 12,000 years of the region’s history. Starting with an overview of what anthropologists and archaeologists do, the reader is next provided with the environmental and climatic history of the Upper Mississippi River Valley region. These overviews show the region as a place where the ancients found all of the necessary elements they needed to live and thrive there throughout 12,000 years of habitation. These sections are very well written and cover topics as diverse as social complexity (I liked the summary chart) to geomorphology, a complex topic the authors make easy to follow with many illustrations and photographs. Next we are given a picture of past archaeological studies done within the region. We find, that at one time, hundreds if not thousands of effigy mounds were spread throughout the area. We are shown hints of the rich archaeological record of the Upper Mississippi River Valley area. The meat-and-potatoes of the volume lay within the eight chapters that outline traditions, or timelines of habitation for the region. Starting with “The First People” (12,000 B.P.) and ending with “The End of Prehistory” (350 B.P. – 0 B.P.) In describing each tradition, the authors tell us a story of life in that time, carefully weaving together the culture history into the descriptions of artifact assemblages. This is different than a lot of archaeological summaries. We are reading about people’s lives much more than just about artifacts and this makes the book very enjoyable as well as informative. An example: “We can learn a great deal about the season of harvest and the habitats exploited by ancient hunters and gatherers by examining specific habitat requirements of ecofacts, such as the discarded mussel shells at Mill Pond. For example, the ebony shell mussel was formerly the most common mussel in the Upper Mississippi River, with many dense populations occurring in beds along the borders of the rivers and its side channels…. Based on inference from the ethnographic record, the ebony shell mussels were probably collected by women wading in the river during midsummer low-water periods. Harvesting experiments indicate that 175 mussels can be collected by one person in an hour at high-density mussel beds. This means that the 3500 mussels recovered from the Early Woodland midden might require as little as 20 hours of harvest time, or five people gathering for a single 4-hour period.” We are never allowed to view just the artifacts or just the data--- the authors keep our attention focused on the people who lived through each and every period of history articulated. Twelve Millennia

is a book meant to solicit interest in archaeology from the public and

also will be of interest to educators and students at all levels. It is

a fine addition to any library of archaeology book, and should be a

must-buy

for anyone interested in the Upper Mississippi Valley. Twelve

Millennia can be ordered direct from the

publisher

for $27.95, by clicking here.

reviewed

by

Bob

Wishoff

|

|

Plaquemine

Archaeology

While

most of the chapters deal with the findings at sites on the Natchez

Bluffs, St.

Charles Parish, East Carroll Parish and the western This is one of the first and one of the very few books out there dealing with the Plaquemine, and is available from the reviewed by Charles

Swenson

|

|

Foraging

in

the Tennessee River Valley 12,500 to 8,000 Years Ago

reviewed

by

Bob

Wishoff

|

|

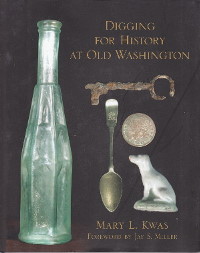

Digging

for History at Old Washington By

Mary L. Kwas University

of

Arkansas Press 2009 1st

ed. ISBN# 1-55728-898-4 cloth hardcover The

town of Washington was located along the Southwest Trail in Hempstead

County in

southwest Arkansas and, in the 19th century, was a thriving

center

of commerce. Fortunately for archaeologists (not so for the town’s

residents),

the town was frozen in time” by a series of calamitous events that

included two

fires, a tornado, and a bypass by the railroads. Now a State Park, the

site has

been extensively studied over the last 25 years—this book presents some

of the

research uncovered by the Arkansas Archaeological survey over the

course of their

studies. Copiously

illustrated,

this book is a fine example of a successful historic archaeology

project. The reader will observe how unknown buildings were discovered,

the

details of construction, and will see artifacts that show day-to-day

life in this

antebellum community. Background information on the site can be viewed

here: http://www.uark.edu/campus-resources/archinfo/atuoldwash.html Digging

for History at Old Washington ($34.95 cloth

hardcover) can be ordered directly from the publisher by clicking here. reviewed

by

Bob

Wishoff

|

|

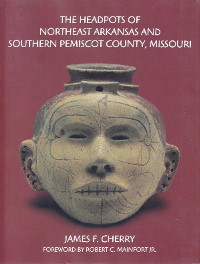

The

Headpots of Northeast Arkansas and southern Pemiscot County, Arkansas By

James F. Cherry University

of

Arkansas Press 2009 1st

ed. ISBN# 1-55728-897-6 cloth hardcover

Mainfort

wrote

that “headpots are perhaps the most distinctive Native American

artifact

found in eastern North America.” There were produced for only 100 years

and

mostly appear in only northeastern Arkansas and extreme southeastern

Missouri. Mainfort

also

noted that “this is an important volume on a number of counts. “A

simple

compendium of the images presented here would, in itself, have been a

publication of value to professional and avocational archaeologists,

museum

curators, art historians, and collectors of pre-Columbian artifacts. At

last,

the complete range of variation in headpots can be seen, appreciated,

and used

by researchers.” But, as Mainfort points out, this book is so much

more. Author

James F. Cherry presents detailed proveniences for each headpot, and

has

compiled geographical distribution maps that will be invaluable to any

researcher interested in Arkansas archaeology. This

beautiful and informative volume ($59.95, cloth hardback) can be

ordered direct

from the publisher by clicking here. reviewed

by

Bob

Wishoff

|

| Home | Gallery | Latest Finds | Back to Main Book Review Index |